Around a year ago, the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) announced that Dr. Hilary Cass, former President of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, would conduct an independent review of transgender youth healthcare services for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the institute in the NHS responsible for evaluating the base evidence behind diagnostic modalities and treatments and then making recommendations regarding which of them should be offered by the NHS. In the UK, transgender medical services are primarily administered through the Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) for Children and Adolescents, which is managed by the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust.

NICE reported its intention to focus on key aspects of care and inform clinical decisions around youth with gender dysphoria. Its review was commissioned specifically to address the “significant increase in the number of referrals [to GIDS] at a time when the service has moved from a psychosocial and psychotherapeutic model to one that also prescribes medical interventions by way of hormone drugs”. Per the terms of reference for review of GIDS, “this has contributed to growing interest in how the NHS should most appropriately assess, diagnose and care for children and young people who present with gender incongruence and gender identity issues”.

The NICE Review of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues (GnRHa), medications that block the production of the sex hormones testosterone and estrogen and are used to treat gender dysphoria in adolescents, was published in March 2021. The review included nine observational studies published no later than October 14, 2020: five retrospective studies, three prospective longitudinal studies, and one cross-sectional study. Authors of the NICE Review evaluated the studies for what they deemed to be “critical outcomes”, including the impact of puberty blockers on gender dysphoria, mental health, and quality of life, and “important outcomes”, defined for purposes of the review as impact on body image, psychosocial health, extent of and satisfaction with surgery, engagement with health care services, and the rate of treatment cessation. Reviewers also examined the evidence base for the short- and long-term safety of GnRHa. These outcomes were used to estimate the clinical effectiveness of treatment with GnRHa medications, which in addition to their roles in treating certain hormone-sensitive cancers (e.g., breast and prostate) also used as puberty blockers in patients with precocious puberty. They also may be used to block puberty in trans adolescents.

The following is an overview of the nine studies examined by the NICE Review authors:

- Vlot et al. 2017: This was a retrospective study of 56 youths on puberty blockers that reported a decrease in bone marrow apparent density (BMAD Z)-scores with GnRHa treatment. An initial decrease of bone mineral density (BMD) scores was observed, followed by normalization or increase of the BMD. BMD assesses bone quality, and a low BMD correlates with an increased risk of bone fracture, while BMAD is a measure of bone mineral density that is primarily used in children, since it accounts for their shorter stature. A Z-score compares your bone density with the average for a person of the same age and sex. According to the International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD), the Z-score in trans youth should be compared with the average for a person of the same age and the gender conforming with the trans youth’s gender identity. In the Vlot et al. study, BMAD remained stable, and the Z-score decrease was expected: GnRHa treatment causes a decrease in bone turnover which coincides with a decrease of BMAD Z-scores.

- Klink et al 2015: This was a longitudinal observational study that followed the treatment of 34 subjects from pubertal blockade to young adulthood. The study reported that trans people treated with GnRHa medications during puberty had lower lumbar spine bone mineral apparent density (BMAD) Z-scores compared with pretreatment levels. Absolute bone mass decreased during puberty blocker monotherapy but increased after the start of gender-affirming hormones. The relevance of this observation to fracture risk was characterized as being unclear.

- Joseph et al 2019: This was a retrospective review of 70 subjects between 12-14 years of age who underwent yearly DXA scans, imaging tests that measure bone density. A progressive decline in BMD and BMAD Z-scores was noted, showing that bone mass does not accrue according to age when puberty is halted. The authors of this study note that it is debatable whether Z-scores remain a valid comparator between youth on blockers and cis youth in puberty given that GnRHa treatment interrupts the rapidity of bone size increase. Be that as it may, no significant change in the absolute values of hip or spine BMD or lumbar spine BMAD over 3 years on puberty blockers was observed, and this result aligns with results of Klink et al. 2015 and Vlot et al 2017.

- Khatchadourian et al. 2014: This was a retrospective review of 84 youth, 27 of whom were treated with puberty blockers. In the study, suicide attempts and emergency room visits for suicidal ideation decreased from 12% at baseline to 5% after the commencement of treatment, which suggested a decrease in suicidality and emotional problems associated with the start of gender-affirming treatment. The authors concluded:

Despite increased public awareness, many clinicians continue to be reluctant to prescribe GnRHa, even though this treatment is strongly recommended as an appropriate intervention for adolescents with gender dysphoria. Our results are encouraging, with only 1 of the 27 patients treated with GnRHa deciding to stop treatment due to emotional lability, and not because of unwillingness to pursue transition… Most experts in transgender care would agree that initiation of GnRHa therapy at an earlier stage of puberty is preferred, because preventing the development of unwanted secondary sexual characteristics can alleviate distress.

- Schagen et al 2016: This was an observational prospective study of 116 patients evaluating the efficacy and safety of puberty blockers. None of the youths discontinued GnRHa treatment because of side effects. Observations included small increases in BMI, with no renal or hepatic complications, consistent with prior studies. An observed decrease in alkaline phosphatase was judged as likely due to decreased bone turnover since no other liver enzyme changes were noted. The authors concluded that Triptorelin, the GnRHa medication reviewed in this study, is effective in suppressing puberty in trans youths, and routine monitoring of liver and kidney function and sex hormone levels is not necessary during treatment.

- Brik et al. 2020: This was a retrospective study of 143 youths undergoing GnRHa treatment. 6% of those who started GnRHa medications discontinued treatment, with 3.5% no longer desiring gender-affirming treatment. None of the subjects discontinued treatment due to potential long-term side effects or lack of information on side effects.

- Costa et al. 2015: This was a longitudinal study of 201 youths at GIDS in London evaluating the effects of puberty suppression on global functioning. The study reported improved global functioning in all subjects who received psychological support and further significant improvement in those who also received GnRHa treatment, observing:

In conclusion, this study confirms the effectiveness of puberty suppression for GD adolescents…The present study, together with previous research, indicate that both psychological support and puberty suppression enable young GD individuals to reach a psychosocial functioning comparable with peers.

- de Vries et al. 2011: This was a longitudinal observational descriptive cohort study of 70 youths on puberty blockers that assessed psychological functioning and gender dysphoria at baseline prior to treatment and shortly before starting gender-affirming hormones. The investigators reported statistically significant decreases in behavioral and emotional problems over time, with less depression, and significant improvement in general functioning. No changes in gender dysphoria, body satisfaction, or feelings of anxiety and anger were reported, leading to the following conclusion:

As expected, puberty suppression did not result in an amelioration of gender dysphoria. Previous studies have shown that only GR (gender reassignment) consisting of CSH (cross-sex hormone) treatment and surgery may end the actual gender dysphoria. None of the gender dysphoric adolescents in this study renounced their wish for GR during puberty suppression.

- Staphorsius et al. 2015: This was a study examining the impact of puberty blockers on executive functioning in 41 trans youths using the ‘Tower of London’ (TOL) task. The TOL task is widely utilized to test executive function, specifically the mental process that enables one to plan. Dysfunction in this area is associated with the frontal lobe of the brain. 8 trans girls on puberty blockers were compared to 10 trans girls not on blockers and 12 trans boys on puberty blockers were compared to 10 trans boys not on blockers. These groups were also compared to controls consisting of 21 cisgender boys and 24 cis girls. The NICE review states that “statistical analysis (of this study) is unclear” and “this study provides very low certainty evidence (with no statistical analysis) on the effects of GnRH analogues on cognitive development or functioning in sex assigned at birth males (transfemales). No conclusions could be drawn.”The results section of this research paper does include statistical analyses on accuracy and reaction times. The authors of this study observed no significant effect of GnRHa treatment on ToL reaction times and accuracy performance scores compared to untreated trans youth with gender dysphoria.The study notes:

In conclusion, our results suggest that there are no detrimental effects of GnRHa on EF (executive function). In addition, we have shed some light on another concern that has been raised among clinicians: whether GnRHa treatment would push adolescents with GD in the direction of their experienced gender. We found no evidence for this and if anything, we found that puberty suppression even seemed to make some aspects of brain functioning more in accordance with the natal sex.

Of note, the NICE Review omitted several studies examining the efficacy and safety of puberty blockers when utilized as part of gender-affirming treatment of transgender youths:

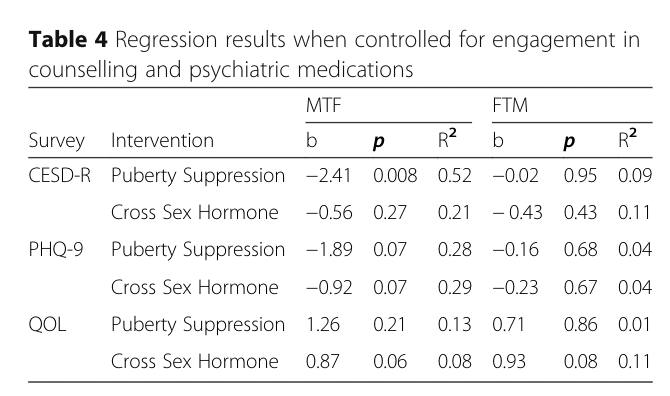

- A 2020 study by Achille et al. on the longitudinal impact of puberty blockers (Epub April 30, 2020) suggested a positive association between gender-affirming treatment and mental health in trans youths, a population they note to be at high risk for suicide and depression. The NICE Review excluded this study because data for GnRHa treatment was not reported separately from other gender-affirming interventions. However, this is incorrect. Results of the regression analysis of this study are shown in the following table:

The authors do note that their sample size was modest, and, in trans females, only puberty suppression reached a significance level of <.05 for the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-R). Associations with the PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire Modified for Teens) and QLES-Q-SF (Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire) scores approached significance. In trans males, only gender-affirming hormones approached statistical significance for quality of life improvement. - Van der Miesen et al. 2020 (published April 6, 2020) conducted a cross-sectional study of 272 adolescents not yet receiving care, comparing them to 178 trans youths receiving affirmative care and 651 cisgender youths. Subjects on blockers were found to have fewer emotional and behavioral problems compared to those trans subjects not receiving medical care. In affirmed subjects, mental health problems and self-harm/suicidality were endorsed at similar rates as for their cisgender peers, a striking result considering that trans youths suffer from a well-documented increased risk of self-harm, suicidality, emotional and behavioral problems, and poorer peer relations as compared to cis youths. The conclusion:

A clinical implication of these findings is the need for worldwide availability of gender-affirmative care, including puberty suppression for transgender adolescents to alleviate mental health problems of transgender adolescents…This first study comparing a group of transgender adolescents just referred for gender-affirmative care, a group of transgender adolescents receiving treatment with puberty suppression, and a group of cisgender adolescents, from the general population showed that when affirmative care involving puberty suppression is provided, transgender adolescents may have comparable mental health levels to their cisgender peers. This type of gender-affirmative care seems thus extremely important for this group.

This study was not mentioned by the NICE Review.

- In 2014, De Vries et al. published a study on trans youths before, during, and after treatment with blockers, and found improved psychological functioning over time, as well as increased quality of life, satisfaction, and happiness. Changes in body image and gender dysphoria were noted only after the addition of hormones and/or gender-affirming surgery. None of the subjects reported regret over any aspect of gender affirmation. The NICE Review omitted this study, using the rationale that the subjects studied had already been discussed in de Vries et al. 2011, even though the newer paper included a longer-term evaluation of the effectiveness and safety of puberty blockers. It is rather odd that the reviewers would leave out a study that addresses one of the chief complaints leveled against gender-affirming care, namely the supposed lack of long term follow-up to assess for long-term effects of the therapy.

- Another neglected paper was by Turban et al., a February 2020 review of a cross-sectional survey of 20,619 trans adults, which reported significantly lower odds of lifetime suicidal ideation in those who received treatment with puberty blockers, compared to those who wanted but did not receive treatment. The NICE Review alleges that data for GnRHa treatment was not reported separately from other interventions in this study, even though the study specifically examined the link between suicidal thoughts and treatment with puberty blockers.

- Kuper et al. 2020 (published April 2020), a longitudinal study examining depression, anxiety, and body image in 148 youths on gender-affirming treatment (including puberty blockers), found large improvements in body dissatisfaction after one year and modest improvements in mental health. Though body image was listed as an important outcome in the NICE Review, this study was not included or even mentioned.

- Schagen et al 2018, a prospective study on 127 trans youths, was excluded by NICE because its outcomes are “not in the PICO” (the measures the reviewers used to assess the evidence presented: P-Population and Indication, I-Intervention, C-Comparator(s), O-Outcomes). I dispute this assessment. The study examined changes in adrenal androgen levels with puberty blockers and/or gender-affirming hormone treatment. The adrenals, as noted by the study, “play a critical role in many different metabolic processes”. It is thus baffling why this study is not included at least under the safety outcomes parameter. The results of the study indicated that despite increases in DHEAS levels and decreases in androstenedione levels in trans boys during GnRHa treatment, there were no negative effects of treatment on adrenal androgen levels at follow-up approximately 4 years later. The changes noted were more likely associated with normal increases during adolescence for the former and reduced ovarian androgen production for the latter.

- Another 2018 study, Swendiman et al., examined Histrelin implants in 377 patients, 34 (9%) of whom were trans. Though the NICE-reviewed Klink et al. study had 34 participants, in this case, this much larger study was excluded because “less than 10% of participants had gender dysphoria; data not reported separately”. The study concludes that Histrelin implants are safe for pubertal hormonal suppression and complications should be expected to occur in approximately 1% of cases.

- Jensen et al. 2019, a retrospective chart review of 85 trans youths, was also excluded for Outcomes not in the PICO. Though the study examined the effects of GnRHa treatment concurrent with gender-affirming hormones, the reviewers do describe the side effects experienced by subjects treated solely with puberty blockers, a parameter which should have qualified for inclusion in the NICE review under safety of treatment. 11 out of 17 subjects on puberty blockers, or 65%, experienced side effects such as hot flashes, mood swings, weight gain, and fatigue. 10 (59%) discontinued treatment with puberty blockers, most commonly due to lapse in insurance coverage. This parameter would also qualify in the NICE Review under their important outcome of “stopping treatment”.

- Another study, Ghelani et al. 2019, excluded for Outcomes not in the PICO, examined the safety of puberty blockers in 36 youths, specifically pertaining to the sudden sex hormone withdrawal these medications induce. The results show no effect of treatment on body composition in trans boys and a significant decrease in lean mass and height in trans girls due most likely to the fact that puberty suppression started at the time when increases in height would be expected in someone not on blockers. As the authors note, this change is often a desirable outcome for trans females. There was no significant change in BMI over the year that the patients were studied.

- Klaver et al. 2018 also examined body composition and shape in trans youths and was also excluded for Outcomes not in the PICO. 192 patients were included in this retrospective review. The study noted that puberty blockers and gender-affirming hormones cause body changes aligned with the patients’ affirmed gender. The authors note:

The findings of this study favor starting treatment in an early stage of puberty, because this appears to be associated with a closer resemblance of body shape to the affirmed sex at 22 years.

- Although the retrospective review study Klaver et al. 2020 (published in March 2020) specifically examined the safety of gender-affirming interventions, it was excluded for Outcomes not in the PICO. However, the study measured blood pressure, BMI changes, lab values including insulin, glucose, and lipids and obesity in 192 trans patients who started GnRHa treatment in their youth and then went on to gender-affirming hormones. Data was obtained prior to GnRHa treatment, prior to hormone addition, and at 22 years old. The study concluded that treatment with blockers and hormones in trans youths is safe in terms of cardiovascular risk factors, however, likely due to numerous factors, obesity was more prevalent in the young adult trans subjects compared to the general population of young adults.

- A 2020 Consensus Parameter published two months after the latest date for publications included in the NICE Review (but before the review was published in March) and engaging 24 international experts reached consensus on 44 expert recommendations for assessing neurodevelopmental effects of puberty blockers in trans youths. The Consensus Parameter noted three longitudinal studies examining puberty blocker outcomes (2 out of 3 included in the NICE Review), and all noted significant improvement in overall psychosocial functioning and lessened depression in youths treated with GnRHa. A cross-sectional study by van der Miesen et al. published April 6, 2020, and also omitted from the NICE Review, reported fewer behavioral and emotional problems in those treated with puberty blockers. Consistent with this result, the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey (omitted from the review) reported a decreased incidence of suicidal ideation in those on puberty blockers compared to those who desired puberty blockers but were unable to access treatment. The Consensus Parameter also makes note of Staphorsius et al., a study assessing impacts of puberty blockers on neural and cognitive functioning, and notes a study by Schneider et al. of one pubertal trans girl on GnRHa who was followed with MRI scans of white matter and cognitive assessments. White matter fractional anisotropy, which indirectly evaluates the integrity and maturation of neurons in the brain, did not increase as otherwise expected during puberty, and at 22 months of treatment, working memory scores dropped by over half a standard deviation. Although large longitudinal studies are needed to further assess the neurodevelopmental impacts of puberty blockers over time, improving mental health can be neuroprotective, and disruption of neurodevelopment may be temporary until sex hormones are introduced back into the body. However, there may be late effects and cognitive findings that have not yet been assessed. The Consensus Parameter serves as a roadmap for future research investigating puberty blockers in trans youths.

- In addition, The Trans Youth Care Study, a longitudinal observational project, has been examining existing medical protocols for trans youths since September 2018, with 90 participants enrolled in the blocker cohort and 301 in the gender-affirming hormone cohort. Preliminary findings have noted better psychosocial functioning in subjects on GnRHa treatment compared to those on gender-affirming hormones, indicating that there could be possible benefits in trans youths accessing gender-affirming treatment earlier in life.

- Vrouenraets et al. 2016, a qualitative study omitted by NICE, asked trans youths themselves about their use of puberty blockers and observed that: (1) the current lack of long-term data was not a problem for them; (2) they did seriously weigh both the short and long-term consequences of puberty blockers and consciously chose treatment; and (3) they were willing to participate in research, showing their insight and altruism. The study stressed the importance of giving a voice to trans youths, since otherwise professionals act based on their assumptions about their views. The NICE Review omitted this study for Outcomes not in the PICO.

Beyond the above omissions (plus more recent data that make the NICE Review assessment of evidence already out of date), it is important to note that, though considered a critical outcome in the review, puberty blockers in and of themselves are unlikely to alleviate gender dysphoria. There are societal and cultural factors that contribute to gender dysphoria, such as bullying at school, barriers to medical care, and family rejection. What puberty blockers do is prevent is the further progression of secondary sex characteristics that develop during puberty, which can ease the distress of trans adolescents regarding their body. As the Gender GP writes, “The pain and distress in adolescents who face prejudice and barriers to living in their authentic gender identity cannot be alleviated by a three-monthly injection alone”.

This is echoed in the one study the NICE Review included that assessed the impact of puberty blockers on gender dysphoria and body image:

As expected, puberty suppression did not result in an amelioration of gender dysphoria. Previous studies have shown that only gender reassignment consisting of CSH (cross sex hormone) treatment and surgery may end the actual gender dysphoria.

An uncontrolled prospective observational study released after the NICE Review, Carmichael et al 2021, examined GnRHa treatment as monotherapy in 44 youths, and found little change in psychological function and BMD changes consistent with suppression of growth. Subjects on blockers reported more happiness and better peer relationships. The researchers noted that gender dysphoria did not improve, which is consistent with the findings of the NICE Review. They explain:

GnRHa does not change the body in the desired direction, but only temporarily prevents further masculinization or feminization. Other studies suggest that changes in body image or satisfaction in GD are largely confined to gender affirming treatments such as cross-sex hormones or surgery.

One of outcomes deemed important in the NICE Review was engagement in healthcare services. Of course, there are many reasons why trans youths, indeed trans people in general, might be reluctant to engage in healthcare services or, having first engaged, choose to disengage from healthcare altogether, including fear of discrimination, exposure to homophobic and transphobic language by staff at clinics, provider prejudice, inappropriate and invasive questions, and being deadnamed or misgendered (called the wrong name or pronoun). One study reviewed noted a large overall loss of patients to follow-up over time but did not report any reasons for the phenomenon. The NICE review also states that there is no evidence for surgical outcomes and gender dysphoria in youths, neglecting a 2018 study on chest dysphoria and surgical outcomes in youths aged 13 to 25 that found statistically higher chest dysphoria scores in those who had not undergone chest reconstruction. More recent studies have yielded similar results.

The NICE review also considers stopping treatment as an important outcome “because there is uncertainty about the short- and long-term safety and adverse effects of GnRH analogues in children and adolescents with gender dysphoria”. This statement ignores history. Puberty blockers have been used to treat precocious puberty for years in children as young as 6 years old, and long-term effects have been studied, with research concluding that GnRHa treatment is effective and safe. Studies on blockers in trans youths have been conducted since the 1980s. In other words, treatment of trans youths with puberty blockers can no longer be considered “experimental”.

The authors of the July 2021 editorial “Access to Care for Transgender and Nonbinary Youth: Ponder This, Innumerable Barriers Exist” posed the following important question:

Given that endocrinologists do not require a mental health assessment prior to using the same medications for other conditions (such as precocious puberty) why should we for transgender and nonbinary youth?

The NICE Review points to a lack of “reliable comparative studies” and “clear, expected outcomes” with GnRHa treatment, citing little change in gender dysphoria and mental health. Other changes attributable to gender-affirming puberty blockers were concluded to be of “questionable” value, with potential for bias and confounding; “…studies all lack appropriate controls who were not receiving GnRH analogues”, according to the NICE Review. Here’s the problem with these statements. There are years of guidelines for gender-affirming puberty blockers in trans youth, such as those used by UCSF, that meet the criterion of evidence-based and are graded according to the GRADE system, a globally recognized measure of evidence based on quality of available studies. This is the same measure that the NICE Review utilized to assess the studies examined. Since gender-affirming treatment is known to be effective in alleviating gender dysphoria, assigning trans youths to a control group who do not receive treatment would arguably be at least ethically dubious, if not outright unethical (e.g. there is a lack of clinical equipoise). Several groups have commented on this very issue with clinical trials in this patient group, including De Vries 2011, a study included in the NICE Review, whose authors observed:

Finally, this study was a longitudinal observational descriptive cohort study. Ideally, a blinded randomized controlled trial design should have been performed. However, it is highly unlikely that adolescents would be motivated to participate. Also, disallowing puberty suppression, resulting in irreversible development of secondary sex characteristics, may be considered unethical.

Dr. Rosenthal notes in his 2014 academic paper, “Furthermore, randomized controlled trials for hormonal interventions in gender-dysphoric youth have not been considered feasible or ethical”. A 2020 study reports that this “particular use cannot be investigated by a RCT”.

One study examined in the NICE Review noted:

A randomized controlled trial in adolescents presenting with gender dysphoria, comparing groups with and without GnRHa treatment, could theoretically shed light on the effect of GnRHa treatment on gender identity development. However, many would consider a trial where the control group is withheld treatment unethical, as the treatment has been used since the nineties and outcome studies although limited have been positive. In addition, it is likely that adolescents will not want to participate in such a trial if this means they will not receive treatment that is available at other centers. Mul et al. (2001) experienced this problem and were unable to include a control group in their study on GnRHa treatment in adopted girls with early puberty because all that were randomized to the control group refused further participation”.

In April 2021, Dr. Helen Webberley reached out to NICE to provide the names and qualifications of the authors of the Evidence Review. The request was refused. As a result, it is impossible to know the identities of the experts who were consulted in composing, assessing, and reviewing the evidence. This is especially concerning given the emergence of trans health ‘experts’ who actively work to remove protections and support for trans people and an utterly unacceptable state of affairs for a review or report produced by a government agency.

Even though no professional organization with trans healthcare expertise opposes the use of puberty blockers to treat trans adolescents, there are those who have interpreted the science of treating trans youths with puberty blockers as experimental and unethical, and those who have noted that “clinicians should proceed with caution,” (p.9, Dahlen et al. International clinical practice guidelines for gender minority/trans people: systematic review and quality assessment). The latter source has unfortunately been cited by those who appear to wish to add roadblocks to gender-affirming care, including Stephen B. Levine, a well-known opponent to gender-affirming care.

Unsurprisingly, the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine (SEGM) has favorably commented on the NICE review of puberty blockers:

In 2020, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) undertook two systematic evidence reviews of the use of GnRH agonists (also known as “puberty blockers”) and cross-sex hormones as treatments for gender dysphoric patients <18 years old. These reviews were commissioned by NHS England, as part of a review of gender dysphoria healthcare led by Dr Hilary Cass OBE. The reviews were published in March 2021.

The review of GnRH agonists (puberty blockers) makes for sobering reading. Its major finding is that GnRH agonists lead to little or no change in gender dysphoria, mental health, body image and psychosocial functioning. In the few studies that did report change, the results could be attributable to bias or chance, or were deemed unreliable. The landmark Dutch study by De Vries et al. (2011) was considered “at high risk of bias,” and of “poor quality overall.” The reviewers suggested that findings of no change may in practice be clinically significant, in view of the possibility that study subjects’ distress might otherwise have increased. The reviewers cautioned that all the studies evaluated had results of “very low” certainty, and were subject to bias and confounding.

In addressing SEGM’s laudatory commentary about NICE, it is worth briefly recounting my own reasons that have led me to my opinion that SEGM is a transphobic organization:

- SEGM describes itself as an “international group of over 100 clinicians and researchers concerned about the lack of quality evidence for the use of hormonal and surgical interventions as first-line treatment for young people with gender dysphoria,” but has been described quite differently by, for example, Mallory Moore and Aviva Stahl, who have described it as having “ties to evangelical activists” and “pushing flawed science,” respectively.

- In an interview with Christian Post Dr. William Malone, an SEGM Clinical and Academic Advisor, has stated, “No child is born in the wrong body, but for a variety of reasons some children and adolescents become convinced that they were.” Dr. Malone and fellow SEGM member Dr. Colin Wright have asserted, “Counseling can help gender dysphoric adolescents resolve any trauma or thought processes that have caused them to desire an opposite sexed body.” In my opinion, these statements are transphobic and reductive and favor a model of care in which children are encouraged to live as their sex assigned at birth. As the American Academy of Pediatrics notes, “conversion” or “reparative” treatment models are used to prevent children and adolescents from identifying as transgender or to dissuade them from exhibiting gender-diverse expressions. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has concluded that any therapeutic intervention with the goal of changing a youth’s gender expression or identity is inappropriate. Reparative approaches have been proven to be not only unsuccessful but also deleterious and are considered outside the mainstream of traditional medical practice.”

- In 2020, Dr. Malone himself testified gave testimony to the Idaho legislature in favor of a bill that would, if passed, have made it a felony for doctors to prescribe hormone blockers for trans people under 18 or to refer them for gender-reassignment surgery. He appears to have been representing himself, not SEGM.

- SEGM has called for amending the criminal code outlawing conversion therapy. Though conversion therapy involves any effort to change sexual orientation and/or gender identity, SEGM President Dr. Roberto D’Angelo justifies SEGM’s opposition by mistakenly claiming that conversion therapy can only be applied to LGB people. This idea is not supported by any major medical organization.

- Dr. Malone wrote a Letter to the Editor of the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism with Andre van Mol, Quentin Van Meter, Michael K. Laidlaw and Paul Hruz. Both Drs. an Meter and van Mol are a members of the American College of Pediatricians (ACP)—indeed Dr. Van Meter is ACP President—a group that has been designated a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, which justifies its designation by pointing out that ACP “opposes adoption by LGBTQ couples, links homosexuality to pedophilia, endorses so-called reparative or sexual orientation conversion therapy for homosexual youth, believes transgender people have a mental illness, and has called transgender health care for youth child abuse.” (Not coincidentally, ACP has also been featured on SBM for promoting some very bad science concluding that Gardasil can cause premature ovarian insufficiency in teenaged girls.) Dr. Malone has also promoted Dr. Laidlaw on Twitter, echoing Dr. Laidlaw’s characterization puberty blockers as a “toxic, harmful, experimental form of conversion therapy for kids who identify as transgender.” (Of note, in the very same article in Christian Post cited above, Dr. Laidlaw was also quoted characterizing puberty blockers as “one of the most insidious child sterilization programs ever devised.”) In addition, Dr. Hruz has also served as expert witness for the Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), which has also been designated a hate group by SPLC for supporting the “recriminalization of sexual acts between consenting LGBTQ adults.”

- SEGM and its members are routinely cited to support anti-transgender legislation and court cases.* It sometimes goes beyond citations as well. For example, SEGM filed an amicus brief arguing for insurance to not cover gender-affirming for transmasculine adolescents, and, in their own words, “providing critical evidence in the Keira Bell case.

- SEGM’s application for a booth at the 2021 American Academy of Pediatrics conference was denied. The AAP, like most other mainstream medical associations, supports gender affirming medical care. They note, “Politics has no place here. Transgender children, like all children, just want to belong.”

- SEGM cites Lisa Littman on their website under “studies,” and many of the other studies listed there reference Littman and her coined phrase, “rapid onset gender dysphoria” (ROGD), which is neither a medical diagnosis nor supported by research.

- *Update 3/5/2022: The recent controversial Texas policy cites SEGM. Twice. In it Texas Governor Greg Abbot cites correspondence with Attorney General Ken Paxton and directs the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services to investigate gender-affirming care for youth in the state, with the interpretation of Texas law that gender-affirming care is “child abuse.” Anyone reported practicing and supporting gender-affirming care for youth could potentially face criminal charges.

The NICE Review and the High Court in London consider the evidence base for youth gender affirmation to be “highly uncertain“. As a result, trans youth in England are in crisis. In addition, there is the question of resources. The GIDS, the UK’s primary trans healthcare service, has only one funded clinic in England and Wales, with a minimum 20 month wait list. Once a youth is established at the clinic, they are subjected to an arduous assessment process lasting a minimum of 3 months and often much longer before treatment begins.

Following the latest legal rulings of the UK High Court, access to puberty blockers has become much more difficult for trans adolescents. All youth under 16 have their cases reviewed on an individual basis by a multidisciplinary clinical review to assess if a referral to GIDS is appropriate. Since the Bell v. Tavistock case in December 2020, GIDS has paused care for new puberty blocker referrals and those assessed to be appropriate for blockers since November 2020 are still waiting to be started on GnRHa treatment.

The UK including NI, has no Transgender adolescent healthcare. It has 'delayed transition' or more accurately @NHSEngland funded conversion therapy. A coercive & systemic approach to delay, rattle, test & prod Trans youth until they can cope with no more. Fight, hide or die.

— TransSafetyNow (@DadTrans) September 3, 2021

The WPATH and its international branches released a statement condemning the Bell v. Tavistock ruling that children under 16 are unable to consent to taking puberty blockers. There is hope, however. On September 17th, the Court of Appeal reversed the judgement in Bell v. Tavistock, forcing the NIH to review its current guidance on puberty blockers and consent. Puberty doesn’t wait, and neither does the high risk of suicide and self-harm in trans youth. Blocking and/or denying access to puberty blockers for trans youth is not a neutral option, as pointed out by Fisher et al., who wrote:

…omitting or delaying treatment is not a neutral option. In fact, some GD (gender dysphoric) adolescents may develop psychiatric problems, suicidality, and social marginalization. With access to specialized GD services, emotional problems, as well as self-harming behavior, may decrease and general functioning may significantly improve. In particular, puberty suppression seems to be beneficial for GD adolescents by relieving their acute suffering and distress and thus improving their quality of life.

The totality of evidence shows that gender-affirming treatment with puberty blockers significantly decreases distress, depression, emotional and behavioral problems and suicidality, while improving global functioning, psychological and psychosocial functioning, quality of life, satisfaction and happiness. There are expected decreases in Z-scores but bone mineral density remains stable on puberty blockers, as does executive function. Adrenal androgen levels change but yield no negative effects at follow-up. Body changes that occur are aligned with the blocked youth’s affirmed gender. Obesity is more common in trans youth, but treatment with blockers does not increase cardiovascular risk factors. More studies are needed on the neurodevelopmental impact of blockers, though the effect of blockers on mental health improvement can be neuroprotective. Research studies continue to confirm that puberty blockers are safe and effective with minimal complications, and that youth do not discontinue blockers due to side effects.

The NICE reviewers fail to account for the studies that explain why gender dysphoria does not improve with puberty blockers, instead considering it a critical outcome of treatment. They omit several important studies that contribute to the knowledge base on trans youth and puberty blockers, and do not acknowledge the many factors that inform engagement of trans people in healthcare services. The NICE review glosses over the extensive history and study of puberty blocker use and ignores the societal, political, and ethical barriers to a robust database of trans health research. As Deutsch et al. note:

…the absence of high-quality evidence should not serve as an immutable barrier to developing meaningful consensus guidelines in a field where societal stigmas have served as the principal underlying reason for the lack of quality evidence.

Those of us involved in transgender healthcare agree that guidelines should meet the same high-quality standards followed by other fields of medicine. For this to happen, we need resources and funding for trans healthcare research, regular and consistent data collection on gender identity, and destigmatization of the trans community. Trans children deserve love, support, and thoughtful medical care as much as cis children do. Trans children are targets in the current political and culture wars; the tide should shift to supporting and protecting this vulnerable population.

*Footnote: This passage was edited by the author on 12/1/2021 for purposes of clarity and disambiguation at the request of the authors of this article that was cited in the original.

The original passage stated: “Even though no professional organization with trans healthcare expertise opposes the use of puberty blockers to treat trans adolescents, there are those who have interpreted the science of treating trans youths with puberty blockers as “experimental” and “unethical”.”